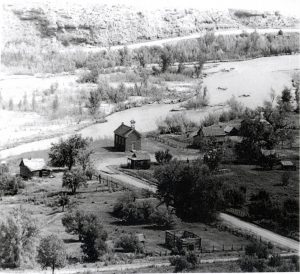

Grafton around 1969

A story about Grafton by Doug Alder on the radio:

Grafton may be a ghost town now, but it still preserves the memory of its former inhabitants. They were hardworking and faithful people who cultivated the land and built these structures. Grafton reminds us of a time when life was challenging but rewarding for those who depended on their beliefs and community. Such bonds between people and place are still alive in the hearts of many of Grafton’s descendants.

Grafton is a rare example of a pioneer village that has not been modernized or destroyed by natural disasters. It offers a glimpse into the past and the hardships and joys of the early settlers. The buildings and features of Grafton have exceptional value in illustrating and interpreting the heritage of this community. They are tangible reminders of people, events, and ideas that have shaped its history.

A list of historic features is as follows:

School House – Built cir 1886

|

|

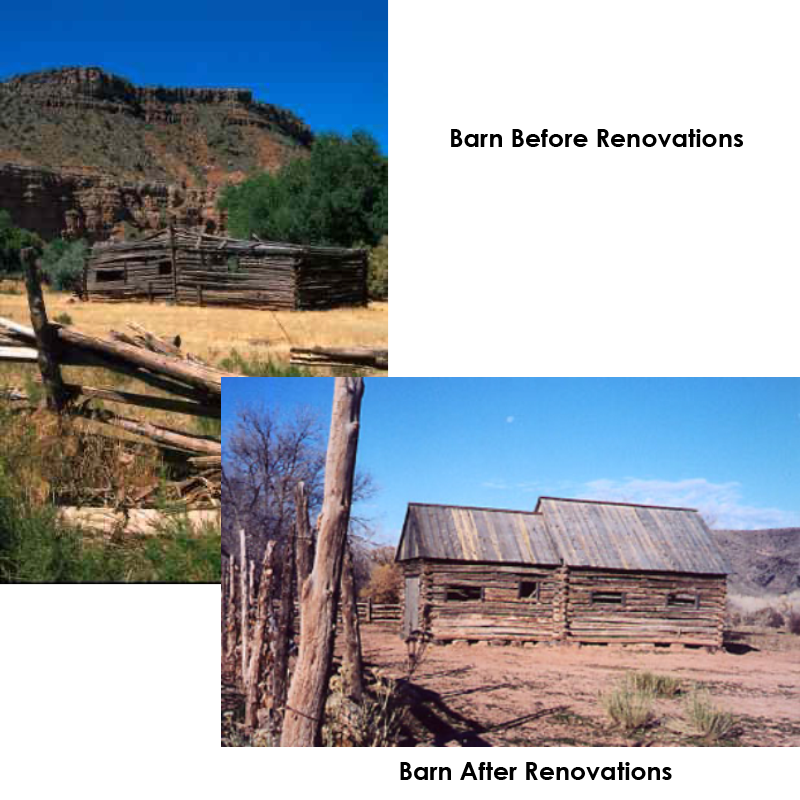

| Before | After |

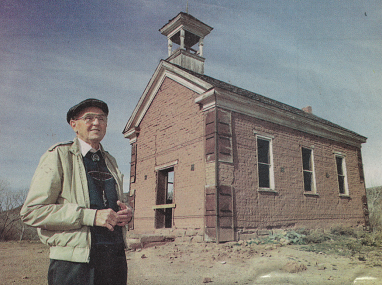

A former resident of Grafton -Lu Wayne Wood- pictured above was born in Grafton 1911 shares a few words:

“The Grafton school/church building was built in 1886 by the dedicated people in this small town to meet their need for a school and church building and to use for social events. It shows what cooperation and togetherness can accomplish through donated labor and material. I think it is symbolic in a larger sense of the faith, determination, and perseverance of those who came and built. Integrity was basic to all of their works and actions.”

Perhaps the most photographed ghost town historic structure in the Western U.S. is this rustic adobe schoolhouse that stands in front of the massive tan and red walls of Zion National Park. The subject of countless movies, paintings, and photographs, the building’s hand-made beauty adds a note of human gracefulness to the outstanding natural beauty that surrounds it.

The Schoolhouse two-story walls stand on a solid foundation of lava rocks quarried from the nearby hillside; its colored adobe bricks were hand-made from a clay pit on the west end of town. The settlers cut trees for this structure from Mount Trumbull, nearly 75 miles away, and bought them across the Arizona Strip and down the steep canyon cliffs of the wood road near the cemetery.

The town’s people used this building as a school, community meeting place, church, and place for dances and plays. People would come from all the settlements on the Upper Virgin River to attend the community dances held on weekends. As was customary with dances in the early west, they continued early into the morning, sometimes until dawn. Then people would hitch up their wagons, buggies, or horses and head back home for Saturday chores and Sunday preparations. The last classes were taught in this building during the 1918-19 school year when enrollment had dwindled to nine students. The following year students were transferred to the school at Rockville.

According to Lyman D. and Karen Platt’s book Grafton, Ghost Town on the Rio Virgin, teacher Mary Beth Woods recalled: “The cowboys liked to come to dances too. They worked out there at Canaan at a big cattle ranch. The Bar Z Company was from Deseret, Milford, and all over up north. They were out there at Canaan and Cane Beds, so they came into Grafton for the dances and social life. Oh, they loved Grafton. They could always sing and dance. Oh, it was really a pleasure to have those guys come.”

Russell Home – Built circa 1888

|

|

| Before | After |

Alonzo Haventon Russell was one of the early settlers of old Grafton, arriving with his wife, Nancy Briggs Foster, and their children in December 1861. Alonzo was the presiding Elder of the Grafton Branch from 1868 to 1877. He survived the great flood of 1862 that destroyed the townsite, and they moved to higher ground, where he built a tent and then three similar log homes for his family. One log home is still standing across from the Russell home. Later, he constructed this adobe house, which still stands today as a testament to his craftsmanship. It was built, and we assume it was built around the same time as the Schoolhouse in 1888 and has been beautifully restored. The front porch was a favorite spot for Alonzo and his family to gather and enjoy music and conversation. Alonzo was a talented musician who played drums and fifer in his family band, the Russell Band. His sons played various instruments, such as fiddles, accordions, guitars, and mandolins. Music and dancing drew the community together. Alonzo was also a skilled blacksmith who provided essential services and products to the town. He made eating utensils, farm tools, fixed wagon parts, sharpened plows, and shod horses. He also devised a way to protect his cattle from Indian raids by making hobbles that the Indians could not remove.

Alonzo had four spouses. His first wife, Fanny Malina Royce, died in childbirth in 1845. He then married Nancy Briggs Foster. Alonzo made a loom for Nancy, and they carried it across the plains. Later it was given to the Pipe Springs National Monument Museum, and a replica can be viewed there today. Alonzo and Nancy had nine children; the last four died as infants. In 1853 Alonzo married Clarissa Henrietta Hardy as a plural wife. She gave birth to three children before their divorce. One of the children died as an infant, and Alonzo and his second wife, Nancy, raised the other two. In 1856 Alonzo married Nancy’s sister, Louisa Maria Foster. Louisa gave birth to nine children. Nancy lived in the large adobe home, and Louisa lived across the street in the small log cabin that had been restored.

When William Thomas Russell married Charlotte Amy Ballard in 1890, Alonzo and Nancy were getting on in years. Alonzo gave this house to William Thomas if he would take care of both Alonzo and Nancy as long as they lived. Then William Thomas Russell moved his family to Hurricane; he sold the house to another son of Alonzo H. Russell, Frank Russell.

Alonzo lived in the adobe home until he died in 1910 at 89; he is buried in the Grafton Cemetery along with his wives, Louisa Maria Foster Russell, and her sister Nancy Briggs Foster Russell.

Alonzo’s son Frank Stephen Russell bought the house for $200 and a cow. Frank and Mary Ellen Ballard Russell moved into the house in 1917 and lived there until they moved to St. George in 1944. They were some of the last residents to leave Grafton.

Reference: FAMILY HOME of ALONZO HAVENTON RUSSELL and NANCY BRIGGS FOSTER, History by James Thomas Jones

https://wchsutah.org/homes/russell-foster-home1.php

Wood Home circa 1877

John Wood Sr. and his wife, Ellen Smith Wood, moved to Grafton in 1877 from England. John was a farmer, raised cattle, worked in a blacksmith shop, and was a craftsman who made beautiful horsehair ropes and hackamores in his spare time. John was also a mason and a carpenter. He was good-humored and a jokester, and Ellen was quick-witted too; everyone enjoyed their company.

First, they built a cellar, a good-sized room in a six-foot hole. In the hole, they baked adobe into bricks for the walls of their house. It was a large home at that time. It had three big rooms with three porches – one in the North, one in the East, and one in the South. On the west were the steps leading down to the cellar. They built a large log barn, a granary, and a historic split-rail fence around the property. All of the structures have been restored.

Since food was scarce, John and the other men went to Long Valley near Orderville, Utah, to plant grain. They had to go out over the Plains and around through Short Creek, Arizona, then back by Kanab, Utah. It took several days to make this journey home.

Ellen died in 1898 at 77 and was buried in Grafton cemetery. He was instrumental in preserving Grafton as a heritage site. John Sr. moved to Hurricane in 1909 and died there in 1911. Their great-grandson LuWayne Wood was born in the Wood house in 1911 and died in 2003 at 92.

Reference: HISTORY OF JOHN WOOD & ELLEN SMITH, Click Here

Wood Family Histories click here.http://larkturnthehearts.blogspot.com/2007/09/growing-up-in-grafton.html

Ballard Home c. 1907

Ballard Home c. 1907

David and Maria Smith Ballard built a home and barn around 1907, which is still standing today. David was born in Rockville in 1867 to John Harvey Ballard and Charlotte Pincock, among the first pioneers to settle in the area. David worked as a cattle rancher, following the primary industry of Grafton, which shifted from cotton to livestock due to the challenges of irrigation and flooding. He died in 1939 at 72 and is buried in Rockville. Maria was born in Rockville in 1867 to Charles N. Smith. She died in Cedar City in 1917 at the age of 50. David and Maria had one son, Jeff Ballard, born in 1898 and lived in Grafton until 1921. David’s father, John Harvey Ballard, was prominent in Grafton’s history. He was a farmer, stock raiser, postmaster, and shoe mender. He was also an excellent violinist and provided music for local communities. He served as a chorister for many years. John and Charlotte had 14 children: 11 sons and three daughters. Only five boys lived to adulthood. John and Charlotte and five of their children are buried in Grafton Cemetery.

The Louisa Marie Russell Home c. 1879

Louisa Marie Russell was the fourth wife of Alonzo Haventon Russell. She gave birth to nine children. Louisa lived across the street in a small log cabin that had been restored. The Louisa Marie Russell Home was built in 1879 by Alonzo for Louisa Maria. It is a one-story gabled log home where Louisa raised six children

Alonzo and his first wife, Nancy returned to Grafton in 1868 after the Indian Troubles; however, his fourth wife, Louisa, remained in Rockville, giving birth to three more children there. She died in 1917 at the age of 77 and is buried in Grafton Cemetery.

Ruby Rose Cabin, built in 2020

Sarah Jane Smith Hastings and William Hastings were among the first settlers of Grafton in 1861. They had eight children and lived a simple life in a wagon box until they bought a dugout from the Romney family. The dugout was a small underground room with a wooden front, door, and two windows. It is now a depression behind this existing cabin.

William passed away in 1882, and Sarah stayed in Grafton, living in the dugout for over five decades. She moved to Hurricane in 1915 and died in 1920 at the age of 90.

According to Lyman D. and Karen Platt’s book Grafton, Ghost Town on the Rio Virgin, a cabin was moved from Blackhorn Flat, north of Parowan, and placed near the dugout site for the movie Ramrod. Sarah never lived in it. The roof started collapsing, and Linda Attiyeh dismantled the log cabin to save the logs. Linda Attiyeh had the cabin rebuilt, and it is across the street from the Schoolhouse in 2020.

A New Restoration in Grafton

–by Linda Attiyeh–

In 1947 a log cabin was moved from Beaver, Utah to the Hastings Dugout lot in Grafton for the movie Ramrod. The cabin interior had plaster walls and used extensively in the movie as Rose’s home and dressmaker shop. My father always called it the Ruby cabin so I will call it the Rudy Rose cabin. My father, Jack Harden fell in love with Grafton. He was born in Salt Lake City and we would drive back and forth from Los Angeles stopping at Grafton. We either forged the Virgin River barefoot, or walked across a board and cable footbridge, or drove across the steel bridge. But we had to open and close many gates all along the dirt road to Grafton.

I remember walking through the log cabin as a teenager. During my childhood I came to think of the cabin as a real gem with just the right proportions. Many years later we purchased the property from Karen who was a member of Ballard family. Gradually overtime the cabin logs collapsed in on themselves. These were beautiful old hand hewn logs made by the pioneers. Weathering has since made these logs even more beautiful. We saved the logs in anticipation that eventually we would restore the log cabin. After thinking about the restoration of the cabin for years we finally decided this year to start the project. We hired expert craftsman Mike Brooks, Brock Wright, and Russell Bezette to work on project using old photographs to make sure the restorations were correct as much as possible. We treated the new wood with vinegar to make it look old. Old windows were remade to fit the windows. We also plan to excavate the Dugout that remains behind the cabin to see what we can find. So thanks to the many who worked on the restoration. This beautiful little hand hewn log cabin has been reborn. –Linda Attiyeh –

The Wood Road

Named for its purpose, the Wood Road was built by settlers in the 1880s and used to bring wood into town for fireplaces and cook stoves. Later when Big Plains became a dry farm, corn and fodder were hauled down the road. The road was used to haul milled lumber from the Mt. Trumbull sawmill some 75 miles away in Arizona. The road follows a deep arroyo from Grafton Cemetery then switchbacks up the mesa. Excavated in the rocky hillside, the wagon trail is fortified by numerous rock retaining walls built by settlers, many of which are located on steep unstable drainages. A substantial wall near the mesa is engineered with wood and rock, and remains in very good condition more than 100 years after it was built. Mr. Lu Wayne Wood remembers, “The road was so steep in places that the descending wagon had to rough locked by use of log chains and a large tree attached behind the wagon as a drag to secure the safety of negotiation of the road.”

A history by Nola I. Jones mentions how James Monroe Ballard remembered, “one time while hauling wood down the steep Grafton Mountain road, the brake lever to the wagon broke. One horse on his team was young and he feared he would become frightened and they would all be killed. He called ‘Woah’ to the horses and the very horse he feared would become frightened, sat down on his haunches while James put rock in front of the wheels to hold the wagon.”

Wooden Berry Fence

|

|

| Before | After |

Grafton Cemetery

(1862-1924)

The Berry headstone found within the wood fenced enclosure near the center of the cemetery reminds us of a time when there wasn�t enough to go around. When the Utah Territory was settled, the upper Virgin River was already inhabited by native Southern Paiute peoples. Pioneers often settled the same places required by these native people for their subsistence. This competition for land and scarce resources led to conflict.

At the same time, Navajo people living south of the Colorado River were squeezed between pioneer settlement in Arizona to the south and Utah to the north. In December 1865, Navajo raiders stole cattle and horses from Kanab and the Shirts ranch at Paria. InJanuary 1866, two ranchers were killed at Pipe Spring and their cattle stolen. Consequently, the Mormon militia killed Indians near Pipe Springs and in retaliation the Indians killed the Berrys, who were traveling home to Berryville (now Glendale on Highway 89), near Colorado City. At the time, Grafton was the County Seat, and their bodies were brought to Grafton for burial.During this time, Mormon Church leader Brigham Young ordered villages in southern Utah to coalesce into towns of at least 150 men. Grafton and other Virgin River towns were deserted as townsfolk consolidated in Rockville. Grafton farmers returned daily to tend their fields, and by 1868, Grafton was resettled and the residents were back, working to create the future.

In the four years after Grafton�s founding in 1862, death came in its usual manner, taking the young, the sick, the old:

Mary Lavina Andrus died at one year of age; Mary Jane York, 28, died of tuberculosis, Byron Lee Bybee, 65, died of �poor health.� And there were accidents: Joseph C. Field, 9, was dragged to death by a horse.

But when the year 1866 hit, the settlers must have wondered if their Heavenly Father had abandoned them. Thirteen people died in rapid succession, taken by epidemics, a tragic accident and by the friction caused when new folks rub up against old. Many headstones are missing. It�s believed 74 to 84 graves exist. The Grafton Cemetery also includes Southern Paiute people who were loved and respected by Grafton residents

The Hard Year of 1866

D AT E, NAME, A G E, C A U S E OF D E AT H

January 18, 1866 John William York 10 years Diphtheria

January 25, 1866 Asa Uriah York 3 years Diphtheria

January 25, 1866 James Jasper York 5 years Diphtheria

February 9, 1866 Frances Ann Field 7 years Diphtheria (Daughter)

February 9, 1866 Sarah Ann Brook Field 37 years Diphtheria (Mother)

February 1866 Sarah Ellen Field 5 years Diphtheria (Daughter)

February 15, 1866 Loretta A. Russell 14 years Accident�Swing Broke

February 15,1866 Elizabeth H. Woodbury 13 years Accident�Swing Broke

April 2, 1866 Robert M. Berry 24 years Killed by Indians (Brother of Joseph)

April 2, 1866 Isabella Hales Berry 20 years Killed by Indians (Robert�s Wife)

April 2, 1866 Joseph S. Berry 22 years Killed by Indians (Brother of Robert)

August 4, 1866 George Judson Andrus 1 year Scarlet Fever

September 1, 1866 Medora Andrus 6 months Scarlet Fever

1866 Else Marie Bybee 45 years Unknown

Robert Madison Berry, 24, his wife Mary Isabella Hales Berry, 20, and brother Joseph Smith Berry, 22, were killed by Navajo raiders.

Today, the cemetery is an historical monument that provides a unique opportunity for area visitors to learn about early pioneer settlement and Grafton’s human history. It serves as a cultural legacy to the many families who are descendents of Grafton settlers.

The cemetery is included as a contributing feature to the proposed “Grafton Historic District”. The Grafton Heritage Partnership (Partnership) entered into a cooperative management agreement with the Bureau of Land Management so that the Partnership can manage the site. The agreement would allow the Partnership to improve existing site conditions by replacing the existing fence surrounding the cemetery with like-kind materials, repair the wood headstone enclosure, install interpretive signage that includes pioneer and Southern Paiute history.

View a Map of the Cemetary with Names

Agricultural Landscape

Agriculture-the most useful, the most healthful, the most noble employment of man. I know of no pursuit in which more important service can be rendered to any country by improving its agriculture.

Agriculture-the most useful, the most healthful, the most noble employment of man. I know of no pursuit in which more important service can be rendered to any country by improving its agriculture.

-Attributed to George Washington, c 1790

Agriculture played an important part of Grafton’s history. The settlers had to live off the land to survive. They built dams across the river and diverted water for cotton and other staple crops. They planted orchards and by 1855 the fruits were used fresh, dried and as preserves. A variety of nut trees were planted making pecans, black walnuts and almonds available. Some of these fruit and nut trees are still alive and producing.

As the years progressed, raising of cattle and other animals became an increasingly important occupation for the early settlers. Nearly every family had at least a few head. Shortly after 1865 they started to change from farming to cattle raising. The harvest in 1866 was from 21 acres of wheat, 45 acres of corn, 18 acres of cotton and 8 acres of sugar cane.

By about 1874, silk production had become common in Grafton. However, as with cotton, silk production lasted only a few years. The settlers were more concerned with growing food crops and were often too busy recovering from floods to concentrate on silk and cotton production.

The Partnership is working with the other landowners in Grafton in order to conserve this agricultural, scenic and historical heritage.

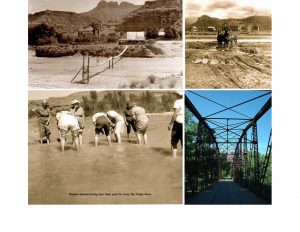

Virgin River

This foot bridge, known as the Swinging Bridge shown above, was one of the ways to cross the river in early days another was by horse team or by wading, as demonstrated by these women at the first Grafton reunion in 1961. In 1924 the Historic Rockville Bridge was constructed that provided another way to get to Grafton.

This foot bridge, known as the Swinging Bridge shown above, was one of the ways to cross the river in early days another was by horse team or by wading, as demonstrated by these women at the first Grafton reunion in 1961. In 1924 the Historic Rockville Bridge was constructed that provided another way to get to Grafton.

A visit to Grafton wouldn’t be complete without a visit to the Virgin River that forms the Townsite’s northern boundary. Pioneers raised garden crops on the few acres of sandy river-deposited soil next to Grafton. Today, these soils support an impressive gallery of trees, plant and wildlife species, including one of only a handful of remaining stands of cottonwood trees anywhere along the Virgin River.

The Partnership is interested in helping manage the floodplain for native plant communities. This will include removing the exotic tamarisk and Russian olive trees and restoring the natural cottonwood, willow, and grass communities…

A restored floodplain with native plants presents an opportunity to interpret Grafton’s natural history, especially as it relates to the town’s human history. It was the river that both gave life to and drove away Grafton’s residents.

Grafton may be a ghost town now, but it still preserves the memory of its former inhabitants. They were hardworking and faithful people who cultivated the land and built these structures. Grafton reminds us of a time when life was challenging but rewarding for those who depended on their beliefs and community. Such bonds between people and place are still alive in the hearts of many of Grafton’s descendants.

Grafton is a rare example of a pioneer village that has not been modernized or destroyed by natural disasters. It offers a glimpse into the past and the hardships and joys of the early settlers. The buildings and features of Grafton have exceptional value in illustrating and interpreting the heritage of this community. They are tangible reminders of people, events, and ideas that have shaped its history.