1847 West of the United States in Mexican Territory

In 1847 a tired group of pioneers stood at Emigration Canyon gazing at the valley of the Great Salt Lake. Their leader, president of the Church of Latter-Day Saints, Brigham Young, said, “This is the place”. The Saints, also known as Mormons, arrived in the Utah Territory after fleeing religious persecution in the United States. There, outside the U.S., Young hoped to establish the “state” of Deseret where Mormons could practice their religion freely. In 1850 after the Mexican American War, Deseret became a U.S. Territory. Between 1847 and 1900, Mormons settled perhaps 500 Mormon villages throughout the west in an effort to claim territory and secure resources for self-sufficiency. Skilled craftsmen and volunteers were called on colonizing missions. For example, in 1851 the villages of Cedar City and Parowan were settled as part of the Iron Mission. Importing iron from the U.S. was difficult and expensive, and when iron deposits were discovered in hills near what is now Cedar City, Young issued the Iron Mission call, and the faithful answered. Brigham Young also reasoned that the warm land south of Cedar City might, if irrigated, produce another costly and U.S.-dependent staple: cotton. He was right. Cotton flourished in an experiment at Santa Clara (1854), and Young sent numerous families to Utah’s “Dixie” as part of the Cotton Mission. To grow cotton, or anything else, pioneers needed two things—land flat enough to farm and water enough to irrigate it—and both were scarce in the Utah Territory. Ten farming settlements grew along the upper Virgin River in the only places they could: Virgin (1857), Grafton (1859), Adventure (1860), Duncans Retreat and Northup (1861), and Shunesburg, Rockville and Springdale (1862).

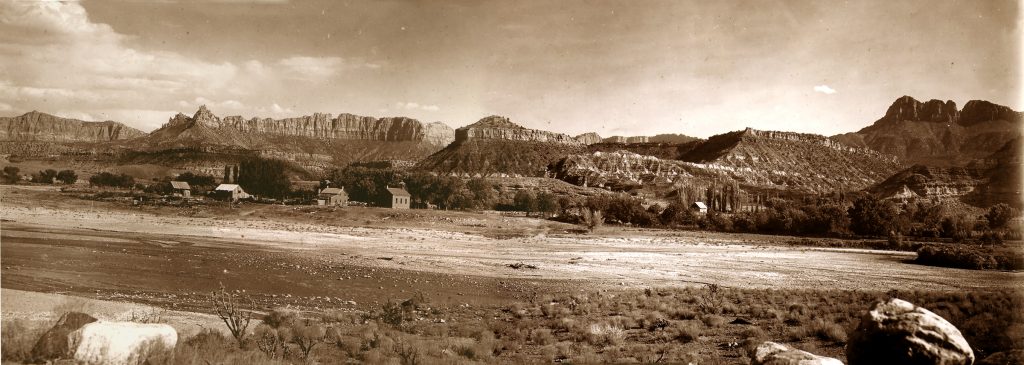

Grafton, Utah Territory, 1859 to 1862

In 1859, Nathan Tenney led five families—the Barney’s, Davies, McFate’s, Platt’s and Shirts—from nearby Virgin to a site one mile downstream of today’s Grafton. The small community cooperated to plant crops, dig irrigation ditches and build homes—the idea was never profit, but rather community and faith. In 1861, as the U.S. Civil War began, cotton became scarce, and Brigham Young’s vision of Utah’s Dixie began to bear fruit.

Grafton was so zealous in its first year cotton of cultivation that farmers didn’t plant enough corn, cane and other crops to feed their families. In coming years Virgin River farmers would scale back cotton in favor of food production. Survival in this arid place alongside a tempestuous river would require their undivided attention and all their land.

Cotton wasn’t the only thing that consumed precious land. In January 1862, a raging flood destroyed most of Grafton, Duncans Retreat, Adventure, and Northup. A resident of Virgin wrote, “the houses in old Grafton came floating down with the furniture, clothing and other property of the inhabitants, some of which was hauled out of the water, including three barrels of molasses.” Grafton’s settlers relocated to higher ground one mile upstream of their first town, where the current townsite now stands. Grafton’s existence is a testament to the early settlers’ perseverance and industrious spirit.

Grafton, Utah Territory, 1862-1866

Even in their new location, Grafton’s troubles were not over. Irrigation dams were repeatedly washed out, sometimes two or three in a single year. Even without flooding, irrigation ditches regularly filled with sand and required such continuous attention that one settler remarked, “making ditches at Grafton is like household washing; it’s a weekly chore!”

Despite Dixie’s limited farmland, scant rainfall and problematic irrigation, Grafton’s settlers were optimistic and, for the most part, in good health. During these years death came in it’s usual manner, taking the old, the sick, and the very young. The Grafton Cemetery holds six babies from these years, all under one year of age. Mary Jane York, 28, died of Consumption (Tuberculosis), and Byron Lee Bybee, 65, died of “poor health.” And there were accidents: Joseph C. Field, 9, was dragged to death by a horse. But life went on. Crops and fruit trees did well and music was a part of everyday life with a dance every Friday night. Grafton grew slowly as Saints from burgeoning Salt Lake City joined the community effort.

During these years, settlements were precarious, and pioneers moved often looking for stable locations. In 1864, a church census showed people distributed along the upper Virgin River as follows. Even by 2000, the population hadn’t grown that much, just rearranged.

Families People (1864) 2000 Census

Virgin City 56 336 394

Duncans Retreat 8 50 —-

Grafton 28 168 —–

Rockville 18 95 247

Northop 3 17 —–

Shunesburg 7 45 —–

Springdale 9 54 457

129 765 1098