1847 West of the United States in Mexican Territory

In 1847 a tired group of pioneers stood at Emigration Canyon gazing at the valley of the Great Salt Lake. Their leader, president of the Church of Latter-Day Saints, Brigham Young, said, “This is the place”. The Saints, also known as Mormons, arrived in the Utah Territory after fleeing religious persecution in the United States. There, outside the U.S., Young hoped to establish the “state” of Deseret where Mormons could practice their religion freely. In 1850 after the Mexican American War, Deseret became a U.S. Territory.

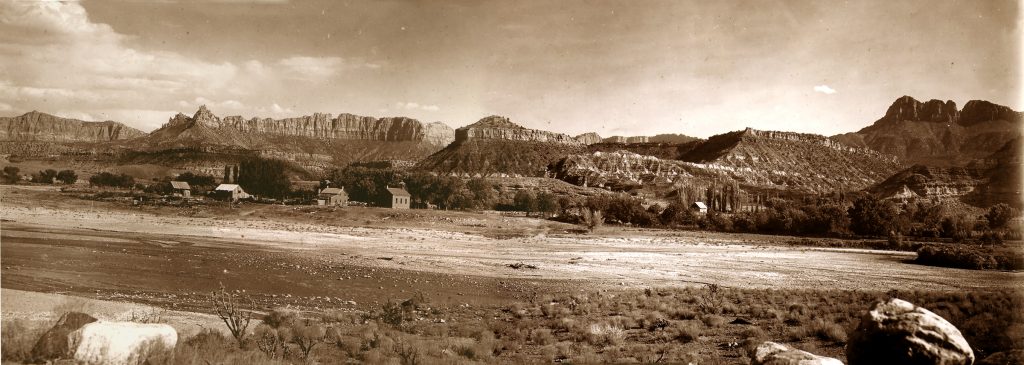

Between 1847 and 1900, Mormons settled perhaps 500 Mormon villages throughout the west in an effort to claim territory and secure resources for self-sufficiency. Skilled craftsmen and volunteers were called on colonizing missions. For example, in 1851 the villages of Cedar City and Parowan were settled as part of the Iron Mission. Importing iron from the U.S. was difficult and expensive, and when iron deposits were discovered in hills near what is now Cedar City, Young issued the Iron Mission call, and the faithful answered. Brigham Young also reasoned that the warm land south of Cedar City might, if irrigated, produce another costly and U.S.-dependent staple: cotton. He was right. Cotton flourished in an experiment at Santa Clara (1854), and Young sent numerous families to Utah’s “Dixie” as part of the Cotton Mission. To grow cotton, or anything else, pioneers needed two things—land flat enough to farm and water enough to irrigate it—and both were scarce in the Utah Territory. Ten farming settlements grew along the upper Virgin River in the only places they could: Virgin (1857), Grafton (1859), Adventure (1860), Duncans Retreat and Northup (1861), and Shunesburg, Rockville and Springdale (1862).

Grafton, Utah Territory, 1859 to 1862

In 1859, Nathan Tenney led five families—the Barney’s, Davies, McFate’s, Platt’s and Shirts—from nearby Virgin to a site one mile downstream of today’s Grafton. The small community cooperated to plant crops, dig irrigation ditches and build homes—the idea was never profit, but rather community and faith. In 1861, as the U.S. Civil War began, cotton became scarce, and Brigham Young’s vision of Utah’s Dixie began to bear fruit.

Grafton was so zealous in its first year cotton of cultivation that farmers didn’t plant enough corn, cane and other crops to feed their families. In coming years Virgin River farmers would scale back cotton in favor of food production. Survival in this arid place alongside a tempestuous river would require their undivided attention and all their land.

Cotton wasn’t the only thing that consumed precious land. In January 1862, a raging flood destroyed most of Grafton, Duncans Retreat, Adventure, and Northup. A resident of Virgin wrote, “the houses in old Grafton came floating down with the furniture, clothing and other property of the inhabitants, some of which was hauled out of the water, including three barrels of molasses.” Grafton’s settlers relocated to higher ground one mile upstream of their first town, where the current townsite now stands. Grafton’s existence is a testament to the early settlers’ perseverance and industrious spirit.

Grafton, Utah Territory, 1862-1866

Even in their new location, Grafton’s troubles were not over. Irrigation dams were repeatedly washed out, sometimes two or three in a single year. Even without flooding, irrigation ditches regularly filled with sand and required such continuous attention that one settler remarked, “making ditches at Grafton is like household washing; it’s a weekly chore!”

Despite Dixie’s limited farmland, scant rainfall and problematic irrigation, Grafton’s settlers were optimistic and, for the most part, in good health. During these years death came in it’s usual manner, taking the old, the sick, and the very young. The Grafton Cemetery holds six babies from these years, all under one year of age. Mary Jane York, 28, died of Consumption (Tuberculosis), and Byron Lee Bybee, 65, died of “poor health.” And there were accidents: Joseph C. Field, 9, was dragged to death by a horse. But life went on. Crops and fruit trees did well and music was a part of everyday life with a dance every Friday night. Grafton grew slowly as Saints from burgeoning Salt Lake City joined the community effort.

During these years, settlements were precarious, and pioneers moved often looking for stable locations. In 1864, a church census showed people distributed along the upper Virgin River as follows. Even by 2000, the population hadn’t grown that much, just rearranged.

Families People (1864) 2000 Census

Virgin City 56 336 394

Duncans Retreat 8 50 —-

Grafton 28 168 —–

Rockville 18 95 247

Northop 3 17 —–

Shunesburg 7 45 —–

Springdale 9 54 457

129 765 1098

Grafton, Utah Territory, 1866-1868

A mere two years latter, in 1866, Grafton became a ghost town for the first time.

When the Utah Territory was settled, the upper Virgin River valley was already inhabited by native Southern Paiute peoples. Pioneers, by necessity, settled the same places required by these preexisting people for their subsistence. This competition for land and scarce resources led to conflict, especially to the north.

At the same time, Navajo people living south of the Colorado River were squeezed between pioneer settlement in Arizona to the south and Utah to the north. In 1866, when Mormon settlers were killed near Colorado City by Navajo raiders, Brigham Young ordered villages in southern Utah to coalesce into towns of at least 150 people. Grafton and other Virgin River towns were deserted as townsfolk consolidated in Rockville. Grafton farmers returned daily to tend their fields, and by 1868, Grafton was resettled as the “Indian Problem” ended. A visit to the Grafton Cemetery will demonstrate that 1866 was indeed a very hard year along the Virgin.

Grafton, Utah Territory, 1868-1945

In 1886 Grafton residents hauled lumber 75 miles from Mount Trumbull and gathered clay from a pit west of town to construct the adobe schoolhouse, which still stands at the heart of Grafton.

In 1896, Utah became a U.S. state, and Grafton bustled until 1906 when a newly built canal delivered Virgin River water to the wide, flat Hurricane bench twenty miles downstream. To escape years of bare subsistence on limited acreage and loss of fields from repeated floods, Grafton’s men helped build the Hurricane Canal, Then many Grafton families packed everything, some even their houses, and moved to Hurricane.

In 1929, the mostly intact and barely inhabited Grafton became the setting for the first outdoor talking movie ever filmed. In Old Arizona starred Warner Baxter (who won the Best Actor Academy Award for this role as The Cisco Kid), Raoul Walsh, Edmund Lowe, and Dorothy Burgess.

Grafton, Utah, United States, 1945

Irrigated land at Grafton was severely limited, and it was all claimed by the first generation of settlers. As children grew up and created families of their own, there was no available farm land, and the young men were forced to look elsewhere to make a living. Without enough children to warrant a school, and lacking culinary water and electricity standard in other communities, Grafton gradually became a ghost town for the second time—and so it remains—uninhabited, but not forgotten.

Grafton’s remaining buildings stand as a place holder, a physical memory of a time and lifeway few living today recall. Towns like this are rare, and becoming rarer. Most pioneer villages either lost their historic heart as they grew into modern towns or were washed away in flash floods. Prompted by family connections and fond memories of wonderful community spirit, former resident families initiate yearly Grafton reunions that continue today on the last Saturday of September. Everyone is welcome and its from 12-2, bring your lunch, hat and stories.

Films Shot in Grafton

In Old Arizona, 1929 (First talkie filmed outdoors) and nominated for five Academy Awards including best Picture. Starring Warner Baxter (who won the Academy Award for this role as The Cisco Kid), Raoul Walsh, Edmund Lowe, and Dorothy Burgess.

In Old Arizona, 1929 (First talkie filmed outdoors) and nominated for five Academy Awards including best Picture. Starring Warner Baxter (who won the Academy Award for this role as The Cisco Kid), Raoul Walsh, Edmund Lowe, and Dorothy Burgess.- The Arizona Kid, 1930. Warner Baxter and Carole Lombard.

- Ramrod, 1947. Starring Joel McCrea, Veronica Lake, Preston Foster, Charles Ruggles, Donald Crisp and Lloyd Bridges.

- Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, 1969. Paul Newman, Robert Redford, Katherine Ross (won four Academy Awards)

- Child Bride of Short Creek, 1981. Diane Lane, Helen Hunt, Christopher Atkins, Conrad Bain.

- The Red Fury, 1984. Wendy Lynne, Calvin Bartlett, Katherine Cannon, Juan Gonzales.

Grafton News 2019 Movies https://graftonheritage.org/grafton-news-2019/

Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid ( 1969) : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

Back & Forth (A Ghost Story) Red Rock Rondo at Grafton Graveyard https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=guDOdqaC

In 1927, a 12-year-old girl named Vilo Demille was playing in a graveyard in Grafton, Utah (a remote town once used as a hideaway by Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) when she saw the ghosts of two girls who had died in a terrible accident in Grafton in 1866. Hear the story told in song for Vilo by members of the musical ensemble Red Rock Rondo – Charlotte Bell, Phillip Bimstein, Hal Cannon, Harold Carr, Flavia Cerviño-Wood, and Kate MacLeod – at the Grafton cemetery in front of the grave of the two girls.

Link to story Ghosts – Grafton Newsletter https://graftonheritage.org/grafton-news-2016/

Selected Timeline

| 1847 | Mormons flee persecution, leave the United States and arrive in what’s now Salt Lake City | ||||

| 1848 | California Gold Rush begins; Salt Lake City benefits from westbound miners | ||||

| 1850 | Utah becomes a U.S. Territory | ||||

| 1851 | Parowan and Cedar City, called the Iron Mission, settled by Mormons from Salt Lake City to develop nearby iron deposits | ||||

| 1851 | San Bernardino (California) settled by Mormons from Salt Lake City | ||||

| 1852 | Fort Harmony, the Indian Mission, settled near present day Santa Clara | ||||

| 1854 | Santa Clara settled | ||||

| 1855 | Las Vegas (Nevada) settled by the Mormons | ||||

| 1857 | Virgin settled | ||||

| 1866 | Abandoned during “Indian Problem” | ||||

| 1857 | Washington settled | ||||

| 1857 | Mountain Meadows Massacre occurs | ||||

| 1858 | Toquerville settled | ||||

| 1859-1862 | Original Grafton settled (about one mile downstream from present townsite) by folks from Virgin | ||||

| 1862 | Destroyed by flood | ||||

| 1860-1862 | Adventure settled (between Grafton and Rockville) | ||||

| 1862 | Destroyed by flood | ||||

| 1861 | Abraham Lincoln elected President | ||||

| 1861 | St. George settled as part of the Cotton Mission | ||||

| 1861 | U.S. Civil War begins | ||||

| 1861-1862 | Duncans Retreat and Northup settled | ||||

| 1862 | Destroyed by flood | ||||

| 1862 | Shunesburg settled | ||||

| 1866 | Abandoned during the Indian Troubles | ||||

| xxxx | Repeatedly damaged by floods, finally abandoned | ||||

| 1862-1866 | Berryville settled (now Glendale) | ||||

| 1866-1871 | Abandoned during the Indian Troubles | ||||

| 1871 | Resettled | ||||

| 1862-1866 | Grafton settled at present site by settlers flooded out of original Grafton site | ||||

| 1866-1868 | Abandoned during Indian Troubles | ||||

| 1868-1945 | Repeatedly damaged by floods, finally abandoned | ||||

| 1862 | Rockville settled by people flooded out of Adventure, and others | ||||

| 1862 | Springdale settled by settlers flooded out of Northup, and others | ||||

| 1864-1866 | Kanab settled | ||||

| 1866-1870 | Abandoned during Indian Troubles | ||||

| 1870 | Kanab resettled | ||||

| 1865 | Lincoln Assassinated; Civil War ends | ||||

| 1879 | Oak Creek settled (near present-day Zion National Park Human History Museum) | ||||

| 1933 | Homes and farms bought by National Park Service | ||||

| 1896 | Utah becomes a U.S. state | ||||

| 1945 | Last resident moves away from Grafton | ||||

Southern Paiute Indians

Jim Jones sent us this Sherratt Library photo, which he believes to be Cedar Pete, Bill or Wiley, and Poinkum who are buried in the Grafton Cemetery. He also found evidence of Poinkum’s family in Ashby Pace of New Harmony history that talks about Poinkum’s family. “”He was a good Indian. He would travel back and forth through here. Poinkum had a boy named Puss and another boy named Wiley.”

Starting above left to right, Cedar Pete (1830-1890); Bill or Wiley, son of Poinkum and Mary (1883-1897); Poinkum (1847-1905); Puss, son of Poinkum and Mary Poinkum was born 1887. Mary is not buried in the cemetery and her picture on left is from Sherratt Library.

Dr. Wesley P. Larsen wrote in his book, Paiute Scrapbook, “Paiute participation was a key element in the white man’s exploration and settlement of southern Utah…… Without their aid, discovery of the best agricultural land, water sources and town sites would have been much slower and probably would have had a heavier toll in lives lost.” Lyman D. and Karen Platt wrote in their book, Grafton, Ghost Town on the Rio Virgin, that “the Indians had lived in the upper Virgin River area long before the pioneers settled it. With the first arrivals the Indians were friendly and assisted them in working their lands and tending their flocks and herd, digging water ditches, cutting firewood, carrying water, finding plants for medicine and other similar chores. Brigham Young, always the practical statesman, argued that it was cheaper to feed the Indians than to fight with them. However, it was not long before these first settlers created resentment with the Indians because they brought many head of cattle, horses and sheep which began to consume the Indians’ food source and this naturally led to hostilities.”

The Black Hawk Indian War was the longest and most destructive conflict between pioneer settlers and Indians in Utah history. The war erupted as a result of the pressures that white expansion brought to Indian populations in Utah. White settlement of Utah altered crucial ecosystems and helped destroy Indian subsistence patterns, which caused starvation. These conditions were almost universal among western Indians during the period, and in this sense the war can be viewed as an expression of the general Indian unrest and warfare that dominated the trans-Mississippi West during the 1860s. Grafton remained the largest settlement in the upper Virgin River with 160 people living there until 1866. The years 1865 to 1867 were by far the most intense of the conflict. During this two-year period residents of Grafton moved to Rockville temporarily for protection as settlements were consolidated, although they continued to farm their fields in Grafton during the day.

In the fall of 1867 Chief Black Hawk made peace and in 1868 families began returning to Grafton. However, less than the pre-evacuation population returned. Peace with the Southern Paiute Indians were finally established and many of them became friends of the Grafton settlers and many Paiutes were loved and respected by Grafton settlers. The Southern Paiute Indians had a camp of tepees above the irrigation ditch south west of town. By the mid 1870s most Southern Paiutes had abandoned efforts to live off the land in the traditional manner and had moved into areas adjoining the communities.

A history of Old Grafton written by James T. Jones.

Reference Materials:

Greer Chesher author and writer, Rockville, Utah, creator of Grafton’s Brochure

Lyman D. and L. Karen Platt, Grafton ,Ghost Town on the Rio Virgin, 1998.

Dr. Wesley P. Larsen, Paiute Scapbook, 2001.

National Register of Historic Places nomination of the “Grafton Historic District” by Polly Hart, March 1, 1999,

Sherratt Library photos, Special Collection